“Hell is a city much like London — A Populous and smoky city” -Shelley

At the later part of the 18th century, as the beginning stages of the industrial revolution began to change the face of country and city life, the increasing use of hydrocarbon fuels including coal, oil and natural gas resulted in one of the unintended consequences of technology: pollution. (http://www.eh-resources.org/timeline/timeline_industrial.html)

In order to run the factories featuring mechanized manufacturing, power source demand quickly outpaced the traditional wind and water supply. While major capital investments were being made to divert rivers, build reservoirs, and develop effective water management schemes the conversion from charcoal to coal outstripped water mills’ impact on industrialization. From coal mining product, steam power could be generated to power a variety of machines.

Unfortunately, coal brought with it air pollution.

In London, a naturally foggy geography combined with industrial smoke earned a reputation for its smog (a combo of smoke and fog); nicknamed “The Big Smoke”, London’s moniker was only slightly less dampening than Edinburgh’s “Auld Reekie.” In the 18th century London had 20 foggy days a year, but this had increased to almost 60 by the end of the 19th century: this meant that London got 40% less sunshine than the surrounding towns, and the number of thunderstorms doubled in London from the early-18th to the late-19th century (The Guardian, 2001) .

In 1873, smog was credited with killing 700 people in London only to be toppled over a decade later by “The Great London Smog of December 1952” which was said to contribute to 4,000 deaths. From the 1800s until the 1950s, air pollution was a little conquered villian of Town.

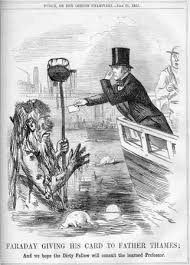

Pollution in the Great Metropolis was not, in itself, a unique or new proposition. Human waste (sewage, rubbish) and industrial waste had long been dumped untreated into the Thames; one incredulous academic wrote in the London Medical Gazette in 1854 that the amount of solid manure produced annually from London’s population amounted to almost 300,000 tons. Outbreaks of cholera and typhoid quickly prompted investment by Parliment in several laws meant to regulate filtration of water…but that didn’t stop 260 tons of raw sewage still being dumped daily into the Thames by 1850. By 1874 engineer Josephy Bazalgette finnaly wrapped on an almost two decade long project for central drainage that was eventually credited with eliminating cholera outbreaks and being an urban pioneer achievement in sewage treament.

Sir Richard Phillips wrote, in A Morning’s Walk from London to Kew, “The Smoke of nearly a million of coal fires, issuing from the two hundred thousand houses which compose London and its vicinity, had been carried in a compact mass in the direction which lay in a right angle from my station. Half a million of chimneys, each vomiting a bushel of smoke per second, had been disgorging themselves for at least six hours of the passing day…In London this smoke is found to blight or destroy all vegetations but, as the vicinity is highly prolific, a smaller quantity of the same residua may be salutary, or the effect may be counteracted by the extra supplies of manure which are afforded by the metropolis.”

Essentially, Phillips is describing the phenomena the US has taken for granted as an L.A. pheonomenon.

He goes on to describe the impact of smog on London, “Other phenomena are produced by its union with fogs, rendering them nearly opagque, and shutting out the light of the sun; it blackens the mud of the streets by its deposit of tar, while the unctuous mixture renders the foot-pavement slippery; and it produces a solemn gloom whenever a sudden change of wind returns over the town.”

Quite the opposite impression, I would say, a naive student of Regencies might have of Town.