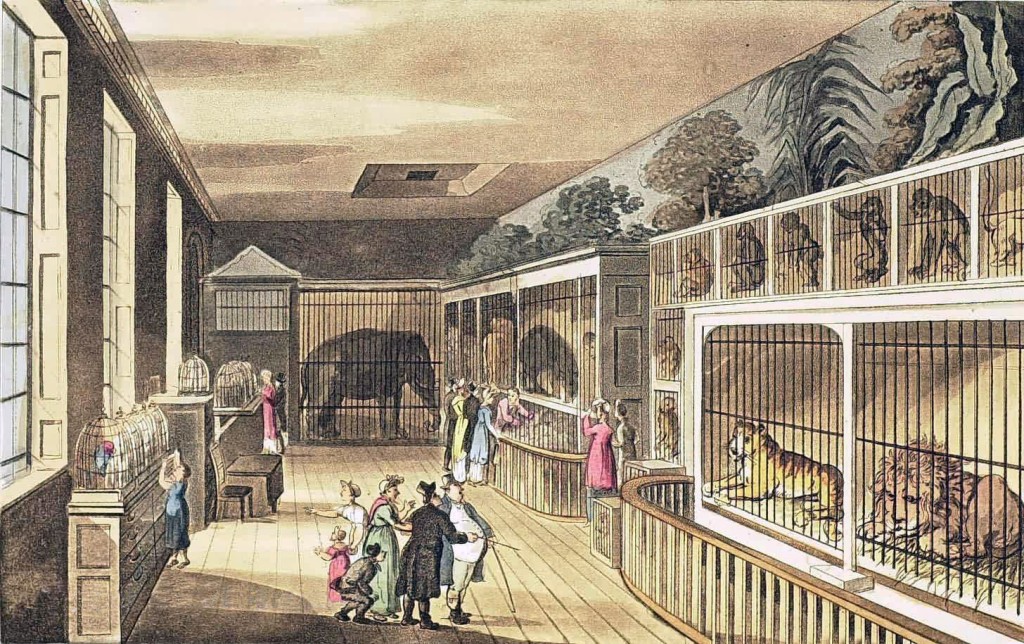

In the Strand the Exeter (Ex)Change was built around 1690 “as a sort of bazaar” which “(l)ike countless other imitations…proved a failure” (London society, Volume 6, 1834, p. 509) Over the years, it held various shops and offices including milliners and upholsterers, until the upper story was “occupied as a menagerie” where beginning in 1773 “the sight-lover had to pay half a crown to see a few animals confined in small dens and cages in rooms of various sizes, the walls painted with exotic scenery to favour the illusion” and the “roar of the Exchange lions and tigers could distinctly be heard in the street, and often frightened horses in the roadway” (London society, Volume 6, 1834, p. 510)

At any time the menagerie might contain lions, tigers, monkeys, kangaroos, an ostrich, rhinos, birds and other exotic creatures for which a visitor paid 1s to view. (London: Being a Complete Guide to the British Capital, 1814).

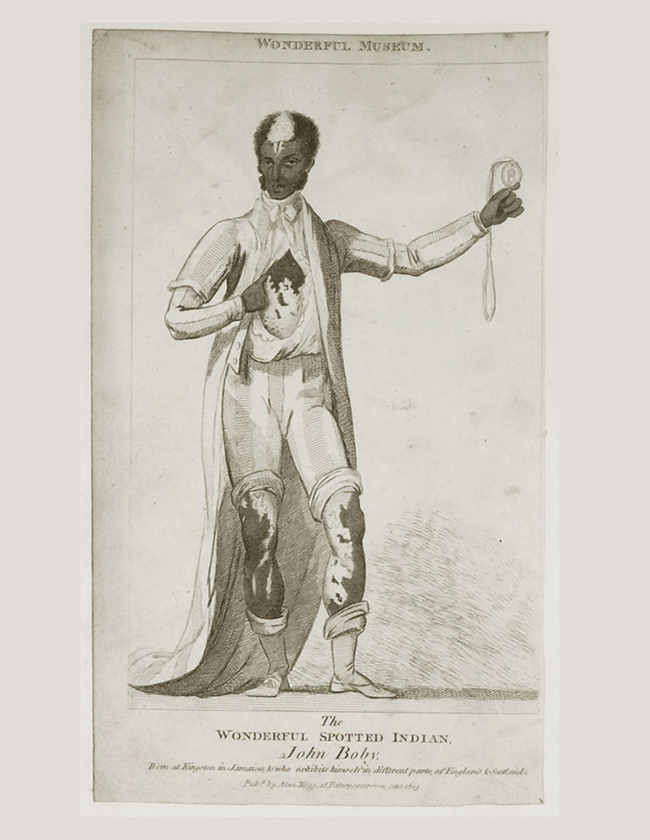

One of the more peculiar exhibits was that of an indentured servant called John Richardson Pimrose Bobey, or Pimrose who was described as “the wonderful Spotted Indian” from Guangaboo in Jamaica (The New Wonderful Museum, and Extraordinary Magazine, 1804). At the museum, John was known as Pimrose. Brought from the West Indies to London as a small child in the 1770s, John had a skin condition, vitiligo, which gave him the appearance of being spotted. Not well understood at the time, vitiligo is now known to be an auto-immune condition.

John’s contract was purchased by one of the proprietors of the menagerie, Thomas Clark in 1789, and made to tend to the animals as well as display himself. When Clark sold his animals to Gilbert Pidock, John was also sold but apparently under protest; “as he was sold, John is credited with protesting, ‘I can’t stand that, I will not be sold like the monkey'” (The Georgian Menagerie: Exotic Animals in Eighteenth-Century London, 2015).

By this time, Bobey had numerous acquaintances and was well versed with British culture. He would stay in the service of Clark for a few months before negotiating a salaried position with Pidock. That only lasted for four months.

Bobey married an Englishwoman who worked for a circus, and pooling their savings purchased their own collection of animals and began to see success with their own traveling menagerie. (The New Wonderful Museum, and Extraordinary Magazine, 1804)

The exchange was popular with poets and painters alike and inspired all sorts of works:London, Past and Present: Its History, Associations, and Traditions, Volume 2, 1891

The menagerie for sometime held a great elephant named Chuni. Evidently, the elephant was quite a character:

The Menageries: Quadrupeds Described and Drawn from Living Subjects, 1831

Chuni also had “achieved theatrical distinction”, performing in the spectacle of Blue Beard at Covent Garden where he was introduced to Edmund Kean. Edmund Kean “kept up an acquaintance” with the elephant. Chuni showed his appreciation for Kean, “whom he would fondle with his trunk” and was rewarded with loaves of bread. (London society, Volume 6, 1834, p. 510)

Chuni became unruly in 1826 and was put to death “by firing ball to the number of 152!” This marked the beginning of the end for the menagerie. The animals were removed to the King’s Mews in 1828, and the entire building was demolished in 1830 to make way for new construction of Trafalgar Square. During the move to Charing Cross, an antelope and hyena escaped but keepers recaptured them “after a furious chase through the London streets” (The Feejee Mermaid and Other Essays in Natural and Unnatural History, 1999)

The Repository of Arts, Literature, Fashions, Manufactures,, January 1818